For decades, a rule of thumb in fitness circles has warned lifters to never let their knees travel beyond their toes when squatting. This advice has been echoed in gyms, textbooks, and training manuals across the world, often without question. But is this long-standing recommendation actually backed by science? Or is it an outdated myth that could be holding your progress back—and even increasing injury risk elsewhere?

As a fitness coach with over 20 years of experience in strength training and injury prevention, I’m here to set the record straight with a deep dive into what the research really says about squatting mechanics, knee travel, and injury risk.

Where the “Knees-Over-Toes” Rule Came From

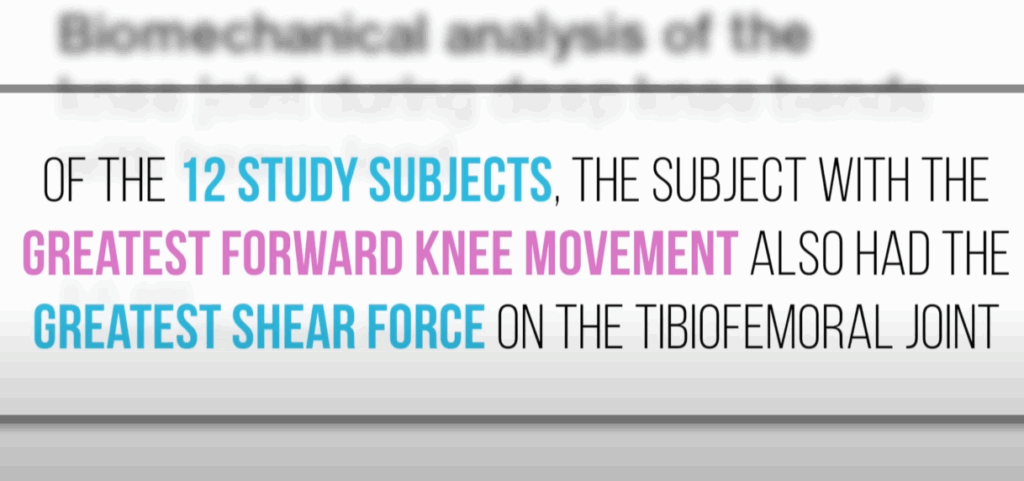

The caution against forward knee travel can be traced back to a 1972 study that linked increased shear force at the knee joint with forward knee displacement during squatting. Specifically, the study found that as the knees moved forward, the tibiofemoral joint (where the shinbone meets the thigh bone) experienced greater shear forces—essentially, opposing forces that could place stress on connective tissues.

However, there’s a problem: that early study lacked critical context. It didn’t control for squat depth, bar position, or torso angle—all of which are vital when assessing joint forces in compound movements like the squat. In fact, it’s likely that a very upright squat posture was used, which can itself change how forces are distributed across the joints.

Real-Life Movement Tells a Different Story

If we take a practical look at daily life, the argument quickly begins to unravel. Think about walking down a flight of stairs—your knees naturally pass your toes, yet healthy individuals rarely experience knee pain doing this. In Olympic weightlifting, athletes often squat into extreme positions with their knees well beyond their toes and maintain long careers without chronic knee issues.

So why is squatting held to a different standard? The truth is that body mechanics are far more complex than a single cue can address.

A Balanced View: Looking Beyond the Knees

One major problem with restricting forward knee movement is that it often shifts the burden elsewhere—namely, the hips and lower back. A pivotal 2003 study by Fry et al. compared two types of squats: one that allowed forward knee travel and one that restricted it using a board. In both cases, lifters squatted to parallel.

Here’s what they found:

- When knees were allowed to travel forward, knee torque increased moderately (150 Nm).

- When knee travel was restricted, hip torque skyrocketed—more than tenfold, from 28 Nm to 302 Nm.

That’s a massive shift in stress away from the knees and onto the hips and spine. The researchers concluded that allowing the knees to move forward is not only acceptable, but necessary for maintaining proper balance and torso positioning during the squat.

This is backed up by additional research suggesting that squats with unrestricted knee movement actually place less strain on the lower back compared to those that force the knees to stay behind the toes.

Practical Guidelines for Safe Squatting

So how should we approach squat form? Rather than obsessing over where your knees are in relation to your toes, focus on the following key principles that apply to most lifters:

- Keep your heels grounded. Your weight should be evenly distributed over your entire foot—especially the midfoot—throughout the movement. If your heels lift, your mechanics are off.

- Track the bar path over the midfoot. When viewed from the side, the barbell should travel in a straight vertical line. This ensures balance and minimizes excessive joint stress.

- Align knees with toes. Your knees should generally point in the same direction as your toes. Avoid allowing them to cave inward (valgus collapse) or flare too far out.

- Use depth that works for your anatomy. While “ass-to-grass” squats are often glorified, not everyone has the mobility or limb proportions for deep squats. Aim to reach at least parallel, but don’t force depth beyond your body’s natural limits.

How Your Body Type Affects Squat Mechanics

Not all squats look the same—and that’s okay. Your anatomy, especially your femur (thigh bone) and tibia (shin bone) length, significantly influences how you squat.

- Long femurs often require a more pronounced forward lean to maintain balance. This naturally leads to more forward knee travel—and that’s fine.

- Torso length and ankle mobility also play roles. If you have limited dorsiflexion (ankle range of motion), your knees may not move forward easily, potentially altering squat depth and form.

There’s no universal perfect squat form—there’s only the best squat for your individual structure.

When the Rule Might Still Apply

While allowing forward knee travel is often beneficial in squats, there are scenarios where you might want to limit it:

- Lunges and split squats allow a more upright torso, so minimizing forward knee movement can help maintain balance and reduce unnecessary strain.

- Existing knee injuries or pain may require temporary modifications to knee position, depending on your rehab goals.

If you’re already dealing with joint pain, it’s best to work with a qualified professional who can assess your mechanics and make personalized recommendations.

Final Thoughts: The Myth Is Busted

The idea that knees should never pass the toes during a squat is overly simplistic and, in many cases, counterproductive. When you restrict knee movement, you may end up placing far greater stress on the hips and lower back—areas that are equally vulnerable to injury.

Proper squat technique should be guided by evidence, not outdated dogma. If your knees move slightly past your toes, that’s often a sign of natural and balanced mechanics—not a red flag.

So ditch the rigid rules and start focusing on proper form that suits your individual body. Your knees—and your progress—will thank you.