Is the Sumo Deadlift Cheating? A Scientific Breakdown of the Controversy

In the world of strength training, few topics stir debate quite like the sumo deadlift. Some lifters dismiss it as a shortcut, claiming it’s an “easier” variation of the conventional deadlift—essentially calling it a cheat. But is there any truth to that criticism? Or is this just gym lore amplified by online echo chambers?

Let’s dig into what the science says, examine lifting data from elite powerlifters, and clarify what really separates sumo from conventional deadlifting.

What’s the Difference Between Sumo and Conventional Deadlifts?

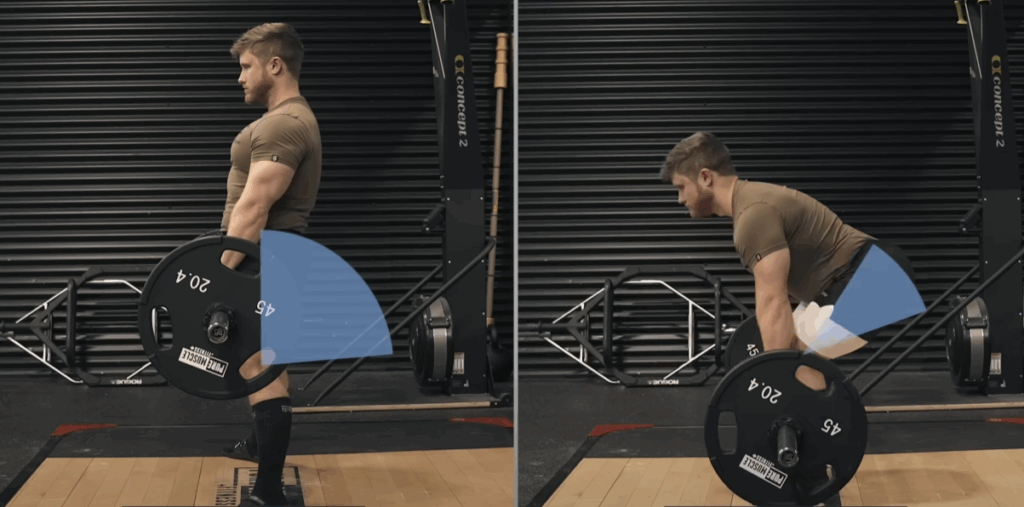

Before diving into the controversy, let’s clarify the mechanics. In a conventional deadlift, the hands grip the bar outside the legs, and the feet are roughly shoulder-width apart. In contrast, the sumo deadlift places the feet much wider, with the hands gripping the bar inside the knees.

Both variations engage key muscle groups like the glutes, hamstrings, spinal erectors, and forearms. The movement involves extending the hips and knees to bring the bar from the floor to a standing lockout.

So why all the fuss about sumo being “cheating”?

The Accusation: “Sumo Is Easier”

The core argument against sumo is that it reduces the range of motion (ROM), making it “less work” and therefore not as legitimate. Critics liken it to doing a partial rep on squats—lifting more weight, but not through the full movement.

However, if sumo really made deadlifting easier for everyone, you’d expect every powerlifter to use it in competition, right?

Elite Powerlifters Tell a Different Story

Data from the International Powerlifting Federation (IPF) reveals that the choice between sumo and conventional varies across weight classes.

In lighter divisions, such as the 59kg or 66kg men’s classes, a large percentage of lifters opt for the sumo stance. But as you move up to the heavyweight and super-heavyweight categories, that trend flips—most lifters there prefer conventional.

This clearly indicates that sumo isn’t universally advantageous. If it were, we’d see it dominate every weight class. But that’s not the case. Instead, lifters choose based on their body structure, mobility, and strength distribution.

Compare this to the bench press, where virtually all elite lifters arch their backs to reduce ROM and maximize power output. That’s a clear competitive advantage almost everyone takes. If sumo offered the same advantage, you’d see the same adoption—but you don’t.

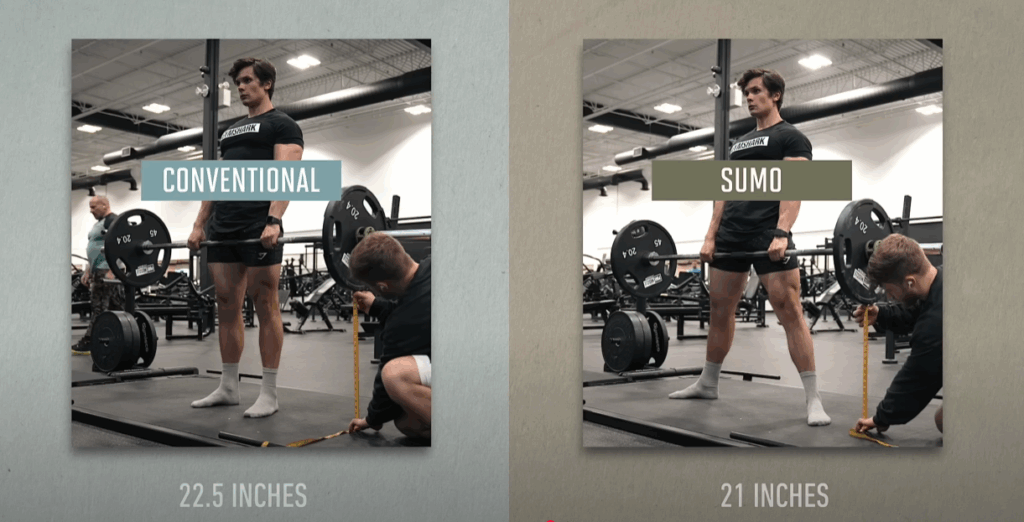

Is Range of Motion Really That Different?

Let’s look at actual numbers. For many lifters, the sumo deadlift shortens bar travel by about 1.5 to 3 inches compared to conventional. That may sound like a big deal, but in practice, it translates to a modest 7–15% reduction in bar path depending on body type.

More importantly, a shorter ROM doesn’t automatically make the lift easier. If a lifter can use sumo mechanics to lift 10–15% more weight, then the overall effort or perceived exertion (RPE) often remains similar. In fact, many lifters don’t lift more with sumo; some are stronger with conventional.

Joint Mechanics: The Real Story Behind the Lift

People often focus on how far the bar travels, but biomechanics isn’t just about the bar. The joint angles and muscle demands also change between the two variations.

In sumo deadlifts, the knees undergo a greater range of motion and start from a more flexed position. This increases quad involvement. In contrast, the conventional deadlift places more emphasis on hip extension, engaging the posterior chain—especially the lower back and hamstrings—more heavily.

Interestingly, research using EMG (electromyography) shows that glute and hamstring activation levels are nearly identical between both styles. The spinal erectors tend to fire more in conventional deadlifts, while the quads are more involved in sumo.

So rather than one being superior or inferior, they simply target the musculature differently.

If Sumo Is Easier, Why Doesn’t Everyone Do It?

We return to the main question: if sumo deadlifting provides an unfair advantage, why isn’t it universally adopted?

The answer lies in individual anatomy. Sumo requires more hip mobility and a certain limb length ratio (e.g., longer torso, shorter femurs) to be truly effective. Lifters with longer legs or limited external hip rotation may find it awkward, uncomfortable, or even weaker than conventional.

In many cases, it takes months of practice to execute a strong, technically sound sumo deadlift. It’s not as easy as just widening your stance and watching the weight fly up.

What About Muscle Building?

For hypertrophy, the range of motion matters—especially through the hardest parts of the lift. With squats, partial reps skip the most demanding range (the bottom), so you often see people doing “ego lifts” without really taxing the muscles fully.

But in deadlifting—both sumo and conventional—the hardest part is usually the start from the floor or the mid-shin area, right before the lockout. And both versions hit these sticking points. So even with a slightly reduced ROM, sumo still challenges the muscles through their most demanding range.

The Verdict: Is It Cheating?

Based on the evidence, calling the sumo deadlift “cheating” just doesn’t hold up. It’s a legal, biomechanically distinct lift with its own pros and cons.

- It’s not a guaranteed way to lift more weight.

- It doesn’t dramatically reduce difficulty.

- It involves different muscular demands.

- It’s chosen (or avoided) based on individual leverages, not as a hack to get ahead.

Ultimately, the best deadlift style is the one that fits your anatomy and goals. Whether you’re training for strength, hypertrophy, or sport performance, both styles have value—and neither is “cheating.”

Should You Pull Sumo or Conventional?

If you’re a smaller-framed lifter or have naturally good hip mobility, sumo might feel more natural and allow better positioning. If you’re tall with long limbs or limited mobility, conventional could be your go-to.

Try both for a few training cycles, and track your performance, comfort, and progression. There’s no reason you can’t use both in your program, even alternating block to block or session to session for variety and full posterior chain development.

Conclusion

Debates in strength training are nothing new, but when it comes to the sumo deadlift, the science is clear: it’s a legitimate variation, not a shortcut. Instead of arguing over which style is “harder,” the focus should be on lifting with proper form, targeting weak points, and making consistent progress.

So whether you pull sumo or conventional, remember—it’s not about the stance. It’s about showing up, working hard, and moving forward.