Full Range of Motion vs. Partial Reps: What’s Best for Muscle Growth?

When it comes to resistance training, one of the most debated topics is how far you should take each rep. Should you use a full range of motion (ROM), pushing the muscle through its entire possible movement? Or should you stick to partial reps that focus only on the “meat” of the movement?

The truth is, both methods have their pros and cons—and understanding when to use each can make a big difference in your progress, whether you’re a beginner lifter or an experienced bodybuilder.

Understanding Range of Motion in Strength Training

In strength training, range of motion refers to the extent a joint moves during an exercise. A full ROM means moving the joint through its entire possible arc—for example, descending all the way into a deep squat and then returning to standing. A partial range means stopping short, either at the bottom, top, or both, and staying within a more limited portion of that movement.

People often fall into two categories when it comes to this topic:

- The “Evidence-Based” Camp – which argues that full ROM is superior for building muscle.

- The “Bro Science” Side – where partial reps are favored for keeping tension on the muscle or lifting heavier loads.

Let’s examine both points of view and the research behind them.

Why Some Lifters Prefer Partial Reps

Partial reps are often seen in hardcore gyms and among elite-level bodybuilders. The rationale behind this approach typically includes:

1. Lifting Heavier Loads

Partial reps allow you to handle more weight. For example, if you usually bench press 185 lbs through a full ROM, you might press 225 lbs if you only lower the bar halfway. This can give the illusion of more intensity—but the problem is that more weight doesn’t always translate to more muscle tension.

What many lifters forget is that hypertrophy (muscle growth) is largely a function of mechanical tension and time under tension. When you reduce ROM, you may increase weight but simultaneously reduce the distance and effort involved. This can actually result in less total volume and lower muscle stimulation.

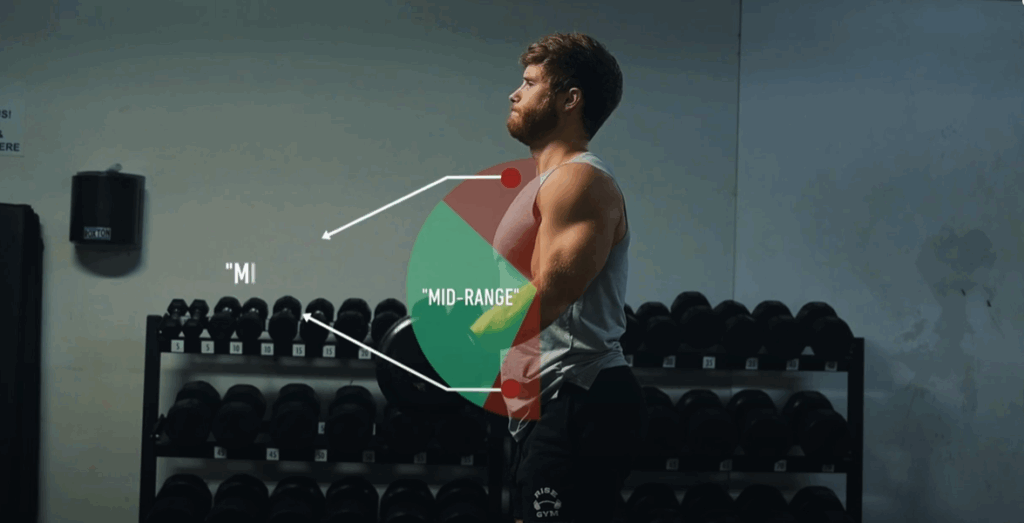

2. Keeping Constant Tension on the Muscle

Now, this is a more valid point. By avoiding the easiest parts of a lift (such as the top lockout or the bottom pause), partial reps can maintain continuous tension on the muscle. Some believe this “burn” is more effective for hypertrophy.

And there is some science backing this up. A 2017 study looked at skull crushers performed with either full ROM or a partial ROM that kept tension in the middle of the movement. Surprisingly, the group using partial reps showed nearly double the muscle growth.

That said, the difference may have been influenced by other factors—such as the partial group training closer to failure. Additionally, this advantage seems to be specific to isolation movements using free weights where tension naturally varies throughout the lift.

Cables and machines, which offer more consistent tension, may not benefit in the same way.

3. Following the Pros

Many modern bodybuilders incorporate partial reps into their training, leading some to believe this technique is superior. But the reality is, professional physiques are the result of a combination of genetics, nutrition, pharmacology, and training volume—not any single method.

Yes, bodybuilders like Ronnie Coleman and Kai Greene have been seen using partials, but they’ve also spent years mastering technique, diet, and programming. Anecdotal evidence, while interesting, doesn’t outweigh well-controlled research.

What the Research Says About Range of Motion and Hypertrophy

To really understand which approach is better, we can look at the current scientific literature. As of now, a systematic review has summarized six key studies on ROM and muscle growth:

- Lower body exercises: All four studies concluded that full ROM produced significantly greater hypertrophy than partial movements.

- Upper body exercises: The results were mixed. One study showed no difference, while another—the skull crusher study mentioned earlier—favored partial reps.

One standout study looked at partial squats with heavier weight versus deep squats with lighter weight. Despite the reduced load, the deep squats led to more muscle growth across the entire quadriceps. This highlights the importance of movement depth, especially in compound leg exercises.

Best Practices for Applying Range of Motion in Your Training

So what does this all mean for your workouts? Here’s how to apply this knowledge practically:

1. Prioritize Full Range for Most Movements

For major compound lifts like squats, deadlifts, and presses, training through a full ROM should be your default. It ensures you’re hitting the muscle across its entire length and maximizing mechanical tension.

This doesn’t mean going to dangerous extremes—don’t force your joints beyond their safe capacity. For example, if your hip structure doesn’t allow for ultra-deep squats, stopping just below parallel is more than enough to stimulate growth.

2. Use Partials as a Supplement, Not a Staple

Partial reps have their place, especially in advanced programs. Some useful applications include:

- Finishing a set: When you can’t complete another full rep, do a few partials to push beyond failure.

- Isolation movements: In exercises like dumbbell lateral raises or flyes, cutting out the easy portion (usually the bottom or top) can help maintain muscle tension.

- Training around injuries: If a full ROM aggravates a joint, partials can keep you in the game while reducing strain.

3. Know When Partials Make Sense in Powerlifting

Powerlifters and strength athletes sometimes shorten their ROM strategically. For example:

- Using an arch in the bench press shortens the distance the bar travels.

- A sumo deadlift reduces ROM compared to conventional style.

While these choices may sacrifice a bit of hypertrophy, they’re valid in a sport where lifting more weight is the main goal.

Final Thoughts: Full Range with Intelligent Exceptions

While partial reps can be useful tools in certain situations, the bulk of your training should still focus on using a full range of motion. This approach has the most scientific backing when it comes to building muscle, especially in the lower body.

However, advanced lifters can benefit from including partial reps sparingly—whether to add variety, finish a tough set, or address specific weak points.

As with most things in training, the best results often come from blending science with experience. Use full ROM as your foundation, and sprinkle in partials where they serve a purpose—not just to lift heavier for the sake of your ego.