, a common misconception has circulated in the fitness world: that serious muscle building requires no scientific understanding, only grit and effort. The sentiment often heard is, “Did Arnold really care about science?” or “Just train hard, eat right, and you’ll see results.” While dedication and consistent effort are undeniably crucial, dismissing the role of science is a disservice to your potential.

Consider this: basic training principles will certainly yield results for most individuals, especially beginners. However, to truly maximize your genetic potential and overcome plateaus, particularly for those who identify as “hard gainers” or advanced lifters, incorporating a scientific approach becomes indispensable. It’s not about replacing hard work with equations, but rather intelligently guiding that effort for superior outcomes.

The argument that historical bodybuilders like Arnold didn’t “do science” is a misnomer. While they may not have had access to peer-reviewed journals in the same way we do today, successful bodybuilders throughout history inherently applied scientific principles through trial and error, observing their bodies’ responses, and refining their methods. The question isn’t whether they needed science, but rather, could they have achieved even greater results with a more formalized, evidence-based approach? I believe the answer is a resounding yes.

Furthermore, an evidence-based approach is often misunderstood. It’s not about rigidly adhering to every scientific study; rather, it’s a three-pronged methodology:

- Best Current Evidence: This involves synthesizing the entire body of available research, understanding its limitations, and assessing the generalizability of findings.

- Personal Expertise: Your own experience as a trainer and your understanding of individual responses are invaluable.

- Individual Needs and Abilities: Recognizing that every person is unique and tailoring strategies to their specific circumstances, genetics, stress levels, nutrition, and sleep.

Research provides foundational guidelines, acting like a sonar in the vast ocean of training possibilities. It helps you navigate in the right direction, ensuring you’re not just “fishing in the dark.” However, it’s crucial to remember that studies often report mean averages, and individual responses can vary wildly. One person might gain 20% muscle from a program, while another gains zero, even on the same regimen. This highlights the profound impact of individual factors and the necessity of personalizing a training plan.

Bridging the Gap: From Lab to Gym Floor

Some practitioners mistakenly believe that if a concept isn’t published on PubMed, it’s invalid. This is just as short-sighted as completely dismissing science. There are invaluable insights gained from years of coaching clients and direct gym experience that may not yet be formally studied. A truly evidence-based practitioner understands this synergy. My own research, for instance, often stems from questions I had during my 18 years as a personal trainer. This practical foundation allows me to investigate topics that directly impact real-world training.

The nuance of applying scientific findings is paramount. For example, a study on sarcopenia in elderly women in a nursing home will have very different generalizability than one conducted on a 22-year-old untrained male. While human physiology shares commonalities, the specifics of training status, recovery capacity, and proximity to genetic limits significantly influence how research translates to individuals. Elite bodybuilders, for instance, are outliers; their responses may differ from those of a typical “trained individual” in a study, who, while disciplined, might not possess the same genetic ceiling or recovery capabilities.

This is why coaching elite athletes becomes an N-of-1 experiment. While general principles serve as a starting point, meticulous observation and adjustment based on individual response are key. It’s about taking those evidence-based guidelines and meticulously applying, manipulating, and refining them for the specific person in front of you.

Exploring Advanced Training Techniques: Insights from “Mountain Dog” Training

Let’s delve into some more advanced training methodologies, specifically drawing from the “Mountain Dog” style popularized by John Meadows, a true legend in the bodybuilding world. Having trained with John, I can attest that his approach, often perceived as solely “blood and gore,” is far more calculated and rooted in scientific principles than many assume.

One notable aspect of his training, which I also incorporate into my own philosophy (as outlined in The Max Muscle Plan), is the concept of building up to a maximal effort set. Instead of taking every working set to failure, John often reserves that all-out intensity for the final set of an exercise. The preceding sets serve as warm-ups and opportunities to establish a strong mind-muscle connection. This approach offers both physiological and psychological benefits. Physiologically, it allows for greater recovery between maximal efforts. Psychologically, it makes the training session more enjoyable and sustainable, preventing the mental fatigue that can set in during multiple heavy sets to failure. This is similar to the periodization of intensity, where failure is a tool to be selectively employed, not a constant.

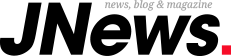

Specialization Techniques: Drop Sets, Rest-Pause, and Eccentrics

Beyond traditional sets and reps, specialized intensity techniques are often employed to push adaptation. Let’s examine a few, especially in the context of scientific evidence:

Drop Sets

Drop sets involve performing a set to failure, then immediately reducing the weight and continuing with more reps to failure. My own collaborative research, while somewhat underpowered, did show a benefit to drop sets using MRI (a gold standard for measurement), even when volume was equated. However, other studies have shown no significant difference when volume is matched.

The practical application of drop sets lies in their ability to add volume efficiently. They allow you to accrue more stimulating reps within a shorter timeframe, making them excellent for time-constrained workouts. If you’re looking to intensify your training without extending your gym session significantly, drop sets are a viable option with no known detriments to muscle growth when compared to traditional training for equal time.

Accentuated Eccentric Training

This technique focuses on the eccentric (lowering) phase of a lift, where muscles are typically stronger. Research suggests that eccentrics provide different intracellular signaling patterns compared to concentric (lifting) training. They also appear to differentially affect hypertrophy across the muscle belly, with some evidence pointing to greater distal hypertrophy from eccentrics.

Incorporating accentuated eccentrics can be done in several ways:

- Two-up, one-down: For exercises like leg curls or leg presses, you can lift the weight with both legs and then lower it with a single leg.

- Spotter-assisted overload: For movements like the bench press, a spotter can help you lift a heavier-than-normal weight (e.g., 120-130% of your 1RM) to the top, and then you control the eccentric lowering on your own.

- Intentional slow negatives: Simply focusing on a slower, more controlled lowering phase can also accentuate the eccentric.

The benefit of accentuated eccentrics lies in their potential to enhance the hypertrophic response through unique stimulus pathways. It’s not about just “frying” the muscle but leveraging its inherent strength during the negative phase to elicit a different, potentially synergistic, growth stimulus. As with any advanced technique, judicious use is key; it’s not meant for every set or every exercise.

The Unsung Hero: Training Technique

While discussions often revolve around training volume, intensity, and frequency, one fundamental element sometimes takes a backseat: training technique. Many assume it’s a given that good form matters, but its true importance often isn’t fully appreciated. Where does it rank in the hierarchy of factors for optimal results?

It’s absolutely critical. Can you still get results with “shitty” technique? To some extent, yes, especially as a beginner. But there’s a spectrum of “bad” technique. For instance, a lateral raise that turns into a front raise primarily targets the anterior delt instead of the medial delt, negating the exercise’s intended purpose. Biomechanical principles and applied anatomy clearly indicate that precise execution maximizes the force generated in the target muscle.

While quantifying the exact percentage of difference good technique makes is challenging, it’s undeniable that proper form ensures the intended muscle group is maximally stimulated. This includes not only the correct kinematic execution of the movement but also minimizing momentum and recruiting synergistic muscles unnecessarily.

Ultimately, training technique is foundational. It ensures that your effort is directed efficiently to the muscles you aim to grow, minimizes injury risk, and allows for progressive overload in a meaningful way. Without it, even the most scientifically sound program will fall short of its potential.

Conclusion

The journey to maximizing muscle gain is a dynamic interplay between scientific principles and practical application. It’s not about choosing one over the other, but rather integrating them to create a highly individualized and effective training approach. By understanding the nuances of evidence-based practice, leveraging advanced training techniques judiciously, and prioritizing impeccable training technique, you can unlock your full genetic potential and consistently drive progress.